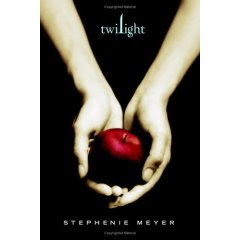

Twilight is the best book I have read in years. I absolutely loved loved loved it, and even better, it has a sequel that's just as good. Stephenie Meyer has written a gripping vampire romance that catches 18 year old Bella on the cusp of adulthood. Bella moves from sunny Phoenix, where she lived with her mom, to the perpetually rainy town of Forks, WA. On the surface, it's just another teen vampire romance; girl goes to new school, meets uncannily pale boy and strange family, falls in love, gets into mortal peril, and is rescued by vampire using his supernatural powers. But oh, it's so much more than that.

Something about the writing in this book just grabbed me and sucked me in emotionally. It helps that Bella is cool, but not too cool; her actions and reactions are absolutely believable, and her incredulity when faced with Edward's nature is perfectly balanced by her I-dont-care-I-love-you teen attitude. This is a book that never even strays into discussing the physical side of teen love, but nevertheless gives you goosebumps as you read about Edward and Bella's first (and supremely dangerous) touch and kiss. The dismal, overcast atmosphere of Forks and environs comes through loud and clear, and it picks up the bittersweet, haunting tone of the writing.

The entire 500 plus pages keeps you trembling on the precipice of first love; I really felt like it was me falling in love for the first time, and that's such an amazing feeling. Somewhere just past the midpoint, Twilight switches its focus from romance to thriller/adventure, and this is where the time spent on developing the characters really pays off. The hunt at the end is certainly well written and executed, but it's impact is made far greater because of the supremely involving (and semi-tragic) love story.

Definitely, absolutely read this book. I could not put it down (even when Rob begged, badgered, and eventually got mad) and when I had binge read its sequel, New Moon, I went out and bought both books and started reading them again. Go NOW and reserve it at the library.